在 遊 山

Une grotte dans la montagne du Ciel,

Séjour des esprits.

Chapelle gravée d'ex-voto; rainures et cupules, par les chasseurs préhistoriques, nos lointains ancêtres.

La grotte t'accueille parce qu'elle est vide et paisible.

Si ton coeur et ton esprit ne sont pas vides et paisibles, comment pourrais-tu accueillir l'Autre ?

石 樹

Les loups du Mercantour et du Québec-Labrador

"La crainte du loup apparaît avec la christianisation. On a été élevés dans une religion de l'agneau. Le loup et l'agneau, cela ne fait pas très bon ménage..."

"Refuser le loup, c'est refuser le diable, c'est refuser la femme, c'est refuser la nature, c'est refuser l'hérétique, c'est refuser tout ce qu'on ne veut pas, quoi !"

"Le loup est là; ça me suffit. Même si je ne le vois pas."

Cette femme très sympathique, intéressante et sensée (en plus d'être une montagnarde et une naturaliste aguerrie), qui fait des recherches sur le comportement des loups dans le Mercantour, filmée et interviewée dans le documentaire télévisé Les Loups du Mercantour, c'est Geneviève Carbone, ancienne élève de mon collègue et voisin au Bâtiment de la Baleine, le Pr. Raymond Pujol, qui occupait la chaire d'Ethnozoologie au Laboratoire d'Ethnobiologie-Biogéographie du Muséum.

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x9fnw6_les-loups-du-mercantour_animals

"L'homme est un loup pour l'homme": on peut se demander quelle est la valeur réelle de cette célèbre formule de l'Antiquité (Plaute)* quand on sait que les loups ont une vie sociale extrêmement importante, raffinée, ritualisée, hiérarchisée, où la communication intense permet de résoudre pacifiquement les conflits. Les loups ne détruisent pas systématiquement leurs semblables et la nature qui les entoure par la bombe atomique, l'agent orange, la pollution, l'esclavage, les camps de concentration, la torture, la misère organisée, etc. Comme tous les prédateurs et Grands prédateurs (le tigre), il exerce un rôle bénéfique sur la nature.

Si l'homme moderne était vraiment un loup pour l'homme, il serait infiniment meilleur et moins méchant et nuisible qu'il ne l'est.

Cette formule est donc fallacieuse car elle prête au loup des défauts et un caractère maléfique qui n'appartiennent en réalité qu'à l'homme, cette espèce dominée par la folie de l'orgueil: l'hybris, la démesure**.

C'est pour cette raison que l'homme a fait du loup son bouc émissaire.

Pierre-Olivier Combelles

Naturaliste, ancien membre du Laboratoire d'Ethnobiologie-Biogéographie du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle.

* "Homo homini lupus". Comédie Asinaria (La Comédie des Ânes, vers 195 av. J.-C).

** http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hybris

Sur la relation entre la langue, la culture et la vie dans la nature chez les Montagnais-Naskapi d'autrefois: "Eka takushameshkui": "Ne mets pas tes raquettes sur les miennes" (Alexis Joveneau, O.M.I., 1926-1991) http://pocombelles.over-blog.com/article-eka-takushameskui-ne-mets-pas-tes-raquettes-sur-les-miennes-alexis-joveneau-o-m-i-1926-1991-111383105.html

Empreinte de loup ("maikan eshinatakushit") sur un sentier emprunté traditionnellement par les Montagnais de La Romaine (Innuat de Ulamen Shipit) à travers la toundra à tourbières et krummholz. Basse Côte-Nord du Québec, août 1993. Photo: Pierre-Olivier Combelles.

Les Indiens Montagnais-Naskapi (Nutshimiu-Innuat: les hommes de l'intérieur des terres et de la forêt) nomment le loup´"maikan" ou "meikan". Ils ne le chassent pas, ne le craignent pas et ne le haïssent pas (cela va ensemble) et ils n'ont jamais cherché à l'exterminer, contrairement à l'homme blanc et aux peuples d'éleveurs. Il faut préciser que les Montagnais-Naskapi sont (ou plutôt étaient, car ils sont sédentarisés depuis 1950) un peuple de chasseurs migrateurs et qu'à l'instar des autres Amérindiens et Inuit du Subarctique et de l'Arctique d'Amérique du nord, ils n'ont jamais domestiqué le caribou, contrairement aux nomades de Sibérie et de Laponie. Les Montagnais m'ont dit que le loup connaît la langue des Indiens, depuis si longtemps qu'il vit à côté d'eux, chassant les mêmes gibiers... Dessin fait par les vieux chasseurs montagnais de La Romaine dans le dictionnaire illustré montagnais-français "Eukun eshi aiamiast ninan ute Ulamen-Shipit" réalisé et publié en mai 1978 par le Comité culturel des Montagnais de La Romaine en collaboration de toute la population de La Romaine (Québec) et sous la direction de feu le Père Alexis Joveneau, O.M.I., curé des Indiens de La Romaine. Photo et archives de Pierre-Olivier Combelles.

Les immensités sauvages de la péninsule du Québec-Labrador: le lac Kahakaukamakaht ("lac étroit"), sur la chaîne des lacs Coacoachou (Basse Côte-Nord du Québec). Lacs, rivières, taïga, toundra, tourbières et monts érodés par les anciens glaciers. J'y entendais parfois le chant lointain et musical des loups. Photo: Pierre-Olivier Combelles (1992) (1993)

"Exister, c'est résister". Quelques pensées de Jacques Ellul (1912-1994)

"Exister, c’est résister".

Devise de Jacques Ellul.

Résister en premier lieu « à la sollicitation du milieu social ». Jacques Ellul, L’Illusion politique, 1965, 3e édition 2004, La Table ronde, p. 297. La formule figure sur la page d'accueil du site de l'Association Internationale Jacques Ellul

« Rien de ce que j’ai fait, vécu, pensé ne se comprend si on ne le réfère pas à la liberté ».

Jacques Ellul, À temps et à contretemps, Entretiens avec Madeleine Garrigou-Lagrange, Paris, Le Centurion, 1981, p. 162.

"Le christianisme est la pire trahison du Christ."

Jacques Ellul, Les successeurs de Marx, cours professé à l’IEP de Bordeaux, 2007, La Table Ronde, p. 153

"Dans l’État communiste, l’homme ne reçoit pour idéal que la production économique et son accroissement. Toute liberté individuelle est supprimée pour la production sociale. Tout le bonheur de l’homme est résumé en deux termes: d’une part « produire plus », d’autre part « le confort".

Jacques Ellul et Bernard Charbonneau, Directives pour un manifeste personnaliste, texte dactylographié édité par les groupes d'Esprit de la région du Sud-ouest ; reproduit en 2003 dans les Cahiers Jacques-Ellul no 1, « Les années personnalistes », p. 68

"Je voudrais rappeler une thèse qui est bien ancienne, mais qui est toujours oubliée et qu'il faut rénover sans cesse, c'est que l'organisation industrielle, comme la « post-industrielle », comme la société technicienne ou informatisée, ne sont pas des systèmes destinés à produire ni des biens de consommation, ni du bien-être, ni une amélioration de la vie des gens, mais uniquement à produire du profit. Exclusivement."

Jaqcues Ellul, Le bluff technologique 1988; seconde édition 2004, Hachette, coll. Pluriel, p. 571.

Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Ellul

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.fr%2Furl%3Fsource%3Dimglanding%26ct%3Dimg%26q%3Dhttp%3A%2F%2Fwebetab.ac-bordeaux.fr%2Fcollege-jacques-ellul%2Ffileadmin%2F0332285E%2Ffichiers_publics%2FJacquesEllul%2FA1-3524587.jpg%26sa%3DX%26ei%3DdmNkVe7kC4aGzAOU0YCwCw%26ved%3D0CAkQ8wc4Fg%26usg%3DAFQjCNHf0IpnrqkZWdCXu8VoA1r4cVklUQ)

Baisaô, le vieil homme qui vendait du thé

« Au pied des collines de Narabi ga Oka vit un homme appelé Baisaô. Il a plus de quatre-vingts ans, en voyant sa tête toute blanche on pourrait croire qu'elle est coiffée de plantes d'armoise tout en désordre. Sa barbe est fort longue et descend plus bas que ses genoux. Portant dans un coffre les instruments nécessaires pour faire du thé, il le fait infuser et le sert aux gens dans les lieux remarquables des monts et des forêts alentour, là où sources et pierres sont pures. Il n'opère aucune distinction entre les personnes de rang important et celle du vulgaire et ne demande jamais s'il sera ou non rétribué pour cela. Il narre avec une douce lenteur les diverses histoires du monde. Ainsi, les gens le trouvent disponible, facile d'accès et éprouvent de la sympathie pour lui. Connu d'une foule de personnes, nonobstant le passage des ans, il ne montre jamais le moindre signe de colère, et tout le monde le tient en grande estime et révérence. Lorsqu'on lui demande quelles sont ses origines, il se contente de répondre : "Je suis un homme des provinces de l'Ouest". Par la suite, un samurai au service du seigneur de Hasuike, dans la province de Hizen, très au fait de sa vie, devait raconter les faits suivants : "Cet homme est le disciple le plus éminent du maître zen Kerin, le supérieur du monastère du Ryûshin-ji. En sa onzième année, il entra en religion, et, sous la houlette de Kerin, il lut les Entretiens et étudia le zen. Passé vingt ans, il pérégrina dans les diverses provinces, et, à travers ses rencontres de maîtres éminents, tels Gekkô en la province d'Ôshû ou Duzhuan de l'école Ôbaku, il raffina sa connaissance de la Voie, puis s'en revint dans les régions de l'Ouest net se retira dans les parages les plus reculés du mont Tonnerre, en la province de Tsukushi. Pour son lever et son coucher, il se tenait dans l'ombre des pins, assis sur les mousses, et il n'avait pour toute nourriture que du blé réduit en poudre qu'il conservait dans une besace qu'il portait toujours avec lui. Pour boisson, l'eau des vallées qu'il puisait lui servait à humecter sa gorge. Il passa ainsi, en méditation assise, tout un été, puis s'en revint à son monastère où il servit Kerin comme de par le passé. Il n'était pas ignorant des enseignements de son école, mais il ne voulut pas reprendre la succession du monastère qu'on lui avait confiée. A la mort de son maître, il remit la charge de l'établissement à son disciple Daichô, et disparut sans qu'on puisse savoir en quel lieu. Mais, aujourd'hui, il vit retiré ici. Il a laissé pousser ses cheveux et il se vêt de vieux vêtements élimés n'ayant l'apparence ni d'un moine, ni d'une personne du vulgaire. Comme je le connaissais au préalable, je lui demandais le pourquoi de son comportement ; il me répondit : 'Ma sagesse et ma vertu sont bien insuffisantes. Dussé-je porter l'habit monastique et recevoir ainsi les dons des gens me considérant digne d'éloge, j'en serai tout contrit de honte, c'est pourquoi j'ai choisi de prendre l'apparence d'un laïc. Depuis toujours, je fus pauvre et, ayant traversé ces dernières années en me contentant de vendre du thé pour vivre, je n'ai jamais eu la moindre envie de prendre femme ou de manger du poisson. Mon coeur jamais ne s'est attaché aux choses de ce monde flottant, j'ai pérégriné et erré sans me fixer en nul lieu précis. Mais, à la capitale, nombreux sont les endroits où la forme des monts,le cours des rivières retiennent mon coeur, c'est pourquoi, sans que j'y puisse mais, mes pas s'y sont arrêtés" ».

Yochiguri monogatari.

In: Lachaud Francois. Le vieil homme qui vendait du thé. Excentriques de Kyōto au XVIIIe siècle. In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 149e année, N. 2, 2005. pp. 629-654.

L'otium literatum selon Pétrarque

La fontaine de la Sorgue. Dessin de la main de Pétrarque, avec la légende: "Transalpina solitudo mea jocundissimo".

Marc Fumaroli à propos de l'idéal de l'existence lettrée tel que le définit Pétrarque (« Académie, Arcadie, Parnasse : trois lieux allégoriques du loisir lettré », dans L'École du silence, Paris, 1994, p. 22. Voir également Le Loisir lettré à l'âge classique, Genève, 1996.) in: Lachaud Francois. Le vieil homme qui vendait du thé. Excentriques de Kyōto au XVIIIe siècle. In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 149e année, N. 2, 2005. pp. 629-654.

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.fr%2Furl%3Fsource%3Dimglanding%26ct%3Dimg%26q%3Dhttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.herodote.net%2FImages%2FPetrarque_maxi.jpg%26sa%3DX%26ei%3D5ZNhVdbkNoW7UcT4gaAI%26ved%3D0CAkQ8wc%26usg%3DAFQjCNHw_BqGSfkZuVVuxeyIitGU0i4FvQ)

Il n'existe aucun conflit entre son humanisme et son christianisme. La vrai foi manqua aux Anciens, c'est vrai, mais lorsqu'on parle vertu, le vieux et le nouveau monde ne sont pas en lutte.

Pier Giorgio Ricci, biographe de Pétrarque.

« Ici j’ai fait ma Rome, mon Athènes, ma patrie». Dans l'une de ses lettres à l'évêque de Cavaillon, Pétrarque explique les raisons de son amour pour la Vallis Clausa : « Exilé d'Italie par les fureurs civiles, je suis venu ici, moitié libre, moitié contraint. Que d'autres aiment les richesses, moi j'aspire à une vie tranquille, il me suffit d'être poète. Que la fortune me conserve, si elle peut, mon petit champ, mon humble toit et mes livres chéris ; qu'elle garde le reste. Les muses, revenues de l'exil, habitent avec moi dans cet asile chéri. »

« Aucun endroit ne convient mieux à mes études. Enfant, j'ai visité Vaucluse, jeune homme j'y revins et cette vallée charmante me réchauffa le cœur dans son sein exposé au soleil ; homme fait, j'ai passé doucement à Vaucluse mes meilleures années et les instants les plus heureux de ma vie. Vieillard, c'est à Vaucluse que je veux mourir dans vos bras. » (Familiarum rerum).

« J'ai acquis là deux jardins qui conviennent on ne peut mieux à mes goûts et à mon plan de vie. J'appelle ordinairement l'un de ces jardins mon Hélicon transalpin, garni d'ombrages, il n'est propre qu'à l'étude et il est consacré à notre Apollon. L'autre jardin, plus voisin de la maison et plus cultivé, est cher à Bacchus. » (Pétrarque à Francesco Nelli, prieur de l'église des Saints-Apôtres à Florence).

Source: l'excellent article consacré à Pétrarque sur Wikipedia: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C3%A9trarque

Le souci de la patrie

Anaxagore

Il était célèbre par sa race et par sa richesse, plus encore par sa grandeur d'âme. La preuve en est qu'il fit don de son héritage aux siens. Ils lui reprochaient de négliger ses biens; il leur répliqua: "Occupez-vous en donc vous-mêmes." Et il s'en détacha finalement pour s'adonner seulement à l'étude de la nature, sans aucun souci de la politique. Un jour on lui disait: "Tu ne t'intéresses donc pas à ta patrie ?" Il répondit en montrant le ciel: "Ne blasphème pas, j'ai le plus grand souci de ma patrie."

Diogène Laërce

Un des plus grands barrages au monde en projet dans l'Amazonie péruvienne (David Hill//Mongabay/The Guardian))

Peru eyes the Amazon for one of world’s most powerful dams

David Hill

May 18, 2015

OTHER REPORTING BY DAVID HILL

Brazilian firm's mega-dam plans in Peru spark major social conflict

http://news.mongabay.com/2015/0511-sri-hill-maranon-river-dam.html

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon

Peru is proposing a huge hydroelectric dam in the Amazon that, if built, will be one of the most powerful on Earth, do significant harm to the environment, and flood the homes of thousands of people.

The proposed mega-dam would be constructed at the Pongo de Manseriche, a spectacular gorge on the free flowing Marañón River, the main source of the Amazon River.

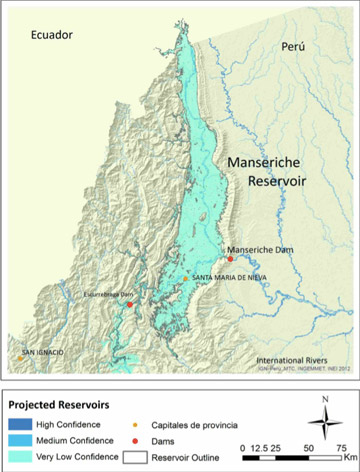

The dam’s reservoir would flood as much as 5,470 square kilometers (2,111 square miles)

and drown the town of Santa Maria de Nieva in the Amazonas department of northern Peru, along with some of neighboring Ecuador, according to an estimate made in a 2014 report by the U.S.-based NGO International Rivers (IR). That estimate was made with admittedly "very low confidence" because of a lack of current available information from Peru’s government.

Santa Maria de Nieva, a small town at the confluence of the Nieva and Marañón rivers that would be flooded by a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

Santa Maria de Nieva, a small town at the confluence of the Nieva and Marañón rivers that would be flooded by a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

Building momentum for the Manseriche dam

Proposals to build a dam at Manseriche have knocked about since at least the 1970s, but current interest is strong, with Peru’s energy sector and president Ollanta Humala touting it as an important upcoming project.

In 2007, Manseriche was slated by the Energy Ministry (MEM) as one of 15 proposed dams that could export electricity to Brazil. Then in 2011, a law declared a Manseriche dam to be in Peru’s "national interest," along with 19 other proposed dams on the Marañón’s main trunk.

Two years later in September 2013, president Humala cited Manseriche as a means of supplying energy to gold and copper mining companies. Speaking at a mining industry conference in Arequipa in southern Peru, Humala declared that: "In order to operate they [the companies] need energy, and for that the construction of at least five hydroelectric power stations generating more than 10,000 megawatts is envisioned." A map depicting Manseriche and four other proposed dams was included in his presentation.

The Pongo de Rentema, the site of one of three proposed dams that would drown Awajun ancestral territory. Photo credit: David Hill

In December 2014, the Manseriche dam was presented as a potential project during the United Nations climate change summit held in Lima, according to Evaristo Nugkuag Ikanan, from the indigenous Awajun people, who would be most impacted by the dam.

"They present these proposals in order to obtain funds for these kinds of projects," explained Nugkuag Ikanan, who works for the Condorcanqui municipality in Nieva.

One local Amazonas government official told Mongabay.com that plans for the Manseriche dam may have progressed even further. He claimed that William Collazos, a MEM representative, made a presentation at a recent internal meeting, revealing that a company has been granted a concession for the dam, which would permit initial work to begin. Neither Collazos nor MEM responded to requests for confirmation.

Might the IDB fund it?

In 2014, scientists from the U.S.-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), conducted research immediately up- and downriver from the Pongo de Manseriche, according to the IDB itself, WCS Peru director Mariana Montoya, and Awajuns living in the region.

The proposed Manseriche dam would flood a 5,470 square kilometer (2,111 square mile) area, including the town of Santa Maria de Nieva and part of neighboring Ecuador, according to an International Rivers estimate. Map credit: International Rivers |

The WCS research is part of a $750,000 IDB "technical cooperation" (TC) project aiming to assess and model the "value of ecosystem services (e.g. spawning habitats and nurseries critical for fish biodiversity and local fisheries), and their likely changes under different hydropower development scenarios" on the Marañón River, the IDB wrote in an emailed statement to Mongabay.com.

The TC project is ultimately "expected to leverage funds for future Bank operations… as well as generate opportunities for future green investments in sustainable hydropower, fisheries and natural or green infrastructure," according to the IDB. As a map sent to Mongabay.com makes clear, the Pongo de Manseriche is one of the main geographical focuses of this research.

However, the IDB informed Mongabay.com that "at present, [it] is not considering any proposed financings of hydroelectric projects in the Marañon River basin, including Pongo de Manseriche." WCS Peru director Mariana Montoya emailed that: "our work is not connected to any proposal to build the dam."

Serious impacts, serious opposition

If Manseriche is built, thousands of indigenous Awajun and Wampis men, women and children would lose their homes and see their land and crops, upon which they depend for survival, flooded.

The Awajuns and Wampis live primarily along the Santiago, Cenepa, Marañon, Nieva, Potro, Apaga and Morona rivers. Nearly the entire Santiago valley, and much of the Nieva and Cenepa valleys, would be flooded by the dam’s reservoir, according to IR’s 2014 report.

Almost every Awajun and Wampis interviewed by Mongabay.com was opposed to, or seriously concerned about, the proposed Manseriche dam. It would, they said, have devastating impacts on migratory fish stocks, flood their homes and crops, and force them from lands to which they have strong cultural and spiritual attachment.

Very large tracts of agriculturally productive land, like these ricefields just upriver from the Pongo de Rentema, would be drowned by Peru's mega-dams on the Marañón River. Photo credit: David Hill

"For us the Pongo de Manseriche is very important for fishing," said Zebelio Kayap Jempekit, president of the Cenepa Frontier Communities Organization (ODECOFROC) representing Awajun communities along the Cenepa River. "Many fish arrive there from Iquitos [a city downriver]. They spend a lot of time there."

Wrays Perez Ramirez, a Wampis man and president of the Permanent Commission of the Awajun and Wampis Peoples (CPPAW), told Mongabay.com that forcing indigenous peoples to leave their homes and land is "genocide" and "ethnocide."

"If they build the dam, the fish are no longer going to migrate upriver," he said. "We live from these resources, from these forests… [and] they’re going to destroy [it all]."

Violent conflict?

Some Awajuns feel the proposed dam could lead to violent conflict and a second "Baguazo," the name given to the initially peaceful protest by thousands of Awajuns and Wampis near the town of Bagua in 2009. Events turned violent there after security forces opened fire on the protesters, leading to more than 200 people being injured and over 30 killed, including more than 20 policemen.

"If they try to dam Manseriche and send in the army, we would be prepared to give our lives in defense of our forest," Edgardo Aushuqui Taqui told Mongabay.com. He is the former vice-president of the Aguaruna Domingush Federation (FAD), which represents Awajun communities immediately upriver from the Pongo, which would be flooded.

Crosses marking the deceased after peaceful protests turned violent near Bagua, Peru in 2009. Some Awajuns say there could be conflict if plans to dam and flood their territories move forward. Photo credit: David Hill

"This will be a second Bagua for us," Aushuqui Taqui said. "I’ve never heard anyone say the dam would be a good thing. Wherever I go, [people] always say the same thing: if [the government and companies] try and go ahead with the dam, they won’t allow it. There is no community you could go to where anyone will say they want the dam. Not one Awajun is going to say we want it."

Cesar Sanchium Kuja, secretary for the Chipe Kusu community on the Cenepa River, said the proposed dam could lead to "very serious" armed conflict.

"We’re never going to allow this dam to be built," he told Mongabay.com. "We’re not going to accept it. This is the only land we have. We don’t have more land. Where would we live? If the government wants to build a dam, it should do it in Lima, with the Rimac [River]. We’re going to annul [this proposal]."

"We can’t let this happen"

Many Awajuns and Wampis interviewed feel similarly to Sanchium Kuja and said they will not permit the Manseriche dam to be built.

"We can’t let this happen," said Roberto Kugkumas Bakuach, FAD’s president. "We won’t allow anyone to do this, not the state nor any company."

"If they build the dam, it’ll flood everything," said Raquel Yampis Petsayit, president of the Indigenous Awajun Women’s Association. "We’ll all die. Our leaders have rejected it."

The town of Bagua, together with neighboring Bagua Grande, would be flooded by the proposed dam at the Pongo de Rentema, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

In previous years, some Awajuns have come together to issue statements denouncing the mega-dam, according to Madolfo Perez Chumpi, president of the Organization for the Economic Development of Awajun Communities on the Marañón (ODECAM), which represents communities between the Pongo de Manseriche and Nieva, which would be inundated.

"We live along the banks of the river," said Perez Chumpi. "Where are we going to plant our manioc? Our plantains? Our maize? Where will we find the fish that swim upriver? This is scary for us, for our children. For the government and the companies, this is development, but it’s not [development] for us. We don’t accept the plan to build a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche."

No consultation, little information

A common complaint of the Awajuns and Wampis interviewed for this article involves the government’s failure to consult with them about the proposed dam, as required by Peruvian and international law. They also resent the lack of available information. Although the 2011 law declaring the Manseriche dam to be in Peru’s "national interest" also states that MEM "will co-ordinate with native communities," local people say that no official has ever visited Awajun or Wampis territory to discuss it.

"There has never been a meeting with the apus [leaders]," said Octavio Shacaime, from the Northern Peruvian Amazon’s Regional Organization for Indigenous Peoples (ORPIAN-P), based in Bagua.

Despite these government failures, there are a few details -- often conflicting – that are available. The 2011 law states that the Manseriche dam would be capable of generating 4,500 megawatt (MW), making it over 5 times more powerful than Peru’s largest existing dam. However, MEM’s 2007 report on exports to Brazil, a 2012 MEM presentation, and the 2013 map shown by president Humala to the mining conference all assert that the dam would generate up to 7,550 MW. That would make Manseriche one of the top 10 most powerful dams in the world, according to Gregory Tracz, from the International Hydropower Association, along with Peter Bosshard, IR’s interim executive director.

The possible precise location of the dam and an extremely vague indication of the area that would be flooded have also been made public. One alternative suggested in MEM’s 2007 report states that the reservoir would not "extend into Ecuadorian territory. A 1976 study puts the height of the dam itself at 126 meters (413 feet).

Map for a project funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) researching the potential impacts of dams on the Marañón River. The Pongo de Manseriche is one of the main focus areas. Map credit: IDB

Some Awajuns and Wampis appear to have a rough idea of the area to be flooded -- knowledge gleaned from IR’s report and other sources. "The priest [now deceased] said that if they dam the Marañón -- especially at the Pongo de Manseriche -- it will flood the entire population along the Santiago, and [the town of] Nieva would disappear," said Amanda Longinote Diaz, president of the Virgin of Fatima Indigenous Women Entrepreneurs Association.

Where the Awajuns and Wampis would be expected to move if the dam is built, or how they would be compensated, is another unknown. No one interviewed said they had any communication from the government regarding this issue.

"Where are we going to live? Where would we go?" asked Longinote Diaz. "Bagua is not a reality for us. Jaen [another nearby town] is not a reality for us. We live from the river, from the forest."

MEM did not respond to questions for this article.

How serious is the threat?

Some people are skeptical as to whether the Manseriche dam can ever be built because it would be so controversial and the social and environmental impacts so devastating.

IR acknowledges in its 2014 report that at 4,500 MW, "the immensity of this project, as currently planned, makes it nonviable." The impacts of a 7,550 MW dam would be even greater.

"I don’t think they’ll ever do it," Peruvian engineer Jose Serra Vega told Mongabay.com. "It’s an old idea. It’s an idea they’ve had forever."

More than just Manseriche

The dam at Manseriche is not the only one that would drown parts of Awajun and Wampis territory. One of the other 19 proposed dams declared in the "national interest" by the 2011 law is planned for the Pongo de Escurrebraga (1,800 MW), upriver from Manseriche. IR’s 2014 report estimated, again with "very low confidence," that this dam would flood 875 square kilometers (337 square miles).

Still another dam declared to be in the "national interest" by the 2011 law is slated for the Pongo de Rentema (1,525 MW), upriver from Escurrebraga.

The spectacular entrance to the Pongo de Rentema, the site of one of more than 20 dams proposed for the main trunk of the Marañón River. Photo credit: David Hill

Rentema and Manseriche are two of the five dams president Humala cited at the 2013 mining conference as providing energy to gold and copper mining companies. According to IR’s 2014 estimate -- also made with "very low confidence" -- Rentema would flood 874 square kilometers (337 square miles) and submerge the towns of Bagua and Bagua Grande.

"Our position is ‘no’ to the three dams downriver from Rentema," said ORPIAN-P’s Octavio Shacaime, who calls the Pongo de Manseriche the Awajun’s "spiritual centre" and compares it to Mecca, The Vatican, St. Peters and Rome. "Every culture has its sacred space. We’ll never allow this to happen. We’ll never consent to this idea."

| This article was produced under Mongabay.org's Special Reporting Initiatives (SRI) program and can be re-published on your web site or in your magazine, newsletter, or newspaper under these terms. |

La voie et la voix des arbres

Chêne pédonculé foudroyé qui a survécu. Dans l'Antiquité, le chêne était l'arbre sacré de Donar-Thor, de Jupiter, dieux du tonnerre, de la foudre et de l'éclair: des forces du Ciel. Photo: Pierre-Olivier Combelles

Esclavagisme : Comment la République française a agi pour maintenir les droits des anciens maîtres esclavagistes (Gilles Devers)

Le gouvernement provisoire n'a pas été imprévoyant. Il s'est rendu compte de tout, il a agi avec un louable empressement, mais sans légèreté, et c'est pour sauver les maîtres qu'il a émancipé les esclaves.

Victor Schoelcher

"Voici, en six chapitres, l’histoire de l’abolition de l’esclavage en France, histoire qui est celle d’une truanderie d’Etat.

Pour sauver ses gigantesques projets de colonisation en Afrique et en Inde - voir Jules Ferry et ses discours sur l'inégalité des races - et pour éviter des révoltes pouvant conduire à l’indépendance, la République a aboli l’esclavage en 1848/1849, par le plus pervers des choix : elle a indemnisé les maîtres esclavagistes, privés de leurs biens qu’étaient les esclaves, en confortant leur pouvoir économique avec un plan d’indemnisation sur 20 ans et consacrant leur possession des terres qu’ils avaient acquises par l'épuration ethnique des indiens Kalinas, les habitants historiques des Antilles. Pendant ce temps, les nouveaux libres, accédant enfin au statut d’être humain, se trouvaient dépouillés de toute indemnisation et de toute ressource. Le jour de leur accès à la citoyenneté républicaine, ils étaient condamnés au plus précaire des salariats.

Les gentils abolitionnistes avaient réussi : le maintien de l’ordre établi, la défense des biens usurpés par les esclavagistes criminels,... et une bonne image de braves humanistes !... Une authentique crapulerie républicaine, et une impunité protégée par l’Etat au fil du temps : à ce jour, les descendants des maîtres esclavagistes restent possesseurs des grands domaines aux Antilles, et les descendants d’esclaves doivent payer pour cultiver les terres sur lesquelles travaillaient déjà leurs aïeuls esclaves, il y a 400 ans… L’organisation par loi de l’impunité, et les miasmes des beaux discours…

Le problème est qu’avec le mécanisme de la Question prioritaire de constitutionnalité (QPC), il devient possible de faire tomber les textes de 1848 et 1849. Et là, le château des mensonges et de la crapulerie va s'écrouler. A prévoir des remises en état et une addition salée.

Chapitre 1 – Un peu d’histoire ancienne

Chapitre 2 – Le cadre juridique de l’esclavage en Guadeloupe

Chapitre 3 – La première abolition, en 1794

Chapitre 4 – Le rétablissement de l’esclavage 1802

Chapitre 5 – L’abolition 1848/1849

Chapitre 6 – Un état du droit universel

Chapitre 7 – La politique de déni de l’Etat français

Chapitre 8 – La responsabilité de l’Etat français"

I – L’esclavage, absent de la tradition française

L’esclavage, la forme la plus sommaire et la plus brutale de l’exploitation de l’homme par l’homme, présente dans le monde dès l’antiquité, ne relève d’aucune tradition juridique française. Les racines historiques de la France se sont construites contre l’esclavage, qui est devenu marginal à partir des V°-VI° siècles, lors de l’écroulement de l’empire romain.

Au Moyen-Age, est apparu le servage qui, aussi redoutable soit-il, était juridiquement distinct de l’esclavage dès lors qu’il était prévu par un statut, que la personnalité juridique du serf était reconnue, de même qu’un minium de droits liés à son travail.

A l’inverse du serf, l’esclave est en droit une chose. Le droit romain n’avait certes jamais retiré la part humaine, car vivante, de l’esclave, mais l’esclave était juridiquement un bien, comme le résume Jean Gaudemet : « L’esclave est un être humain. Le droit ne peut l’ignorer, alors même qu’il lui refuse l’octroi de prérogatives juridiques. Être humain, l’esclave est doué d’une vie affective. Il a une activité économique, des possibilités de travail, manuel ou intellectuel, que son maître sait utiliser et que le droit doit prendre en compte » (J. Gaudemet, « Membrum, persona, status », Studia et Documenta Historiae et Iuris, 1995, n° LXI, p. 2, G. Bigot, « Esclavage », Dictionnaire de culture juridique, dir. D. Alland et S. Rialas, PUF, 2003).

II – La réapparition de l’esclavage en lien avec la colonisation des Caraïbes, au XVI°

L’esclavage moderne, celui qui était lié à la colonisation pour l’exploitation des terres conquises, essentiellement dans les Caraïbes, a réellement pris un nouvel essor en Occident, au XV° avec le Portugal, suivi de l’Espagne, l’Angleterre – puis la Grande-Bretagne, les Provinces-Unies, puis la Hollande. Le consensus était général, l’Eglise donnant son accord par une bulle du Pape Nicolas V, le 8 janvier 1454.

Les abus étaient terrifiants, amenant le Pape Paul III, dès le 2 juin 1537, par sa lettre Veritas ipsa, a posé l’interdit de l’esclavage. Une consigne bien mal appliquée, mais qui établit nettement la conscience du fait illicite :

« Nous décidons et déclarons, par les présentes lettres, en vertu de Notre Autorité apostolique, que lesdits Indiens et tous les autres peuples qui parviendraient dans l'avenir à la connaissance des chrétiens, même s'ils vivent hors de la foi ou sont originaires d'autres contrées, peuvent librement et licitement user, posséder et jouir de la liberté et de la propriété de leurs biens, et ne doivent pas être réduits en esclavage. Toute mesure prise en contradiction avec ces principes est abrogée et invalidée ».

La région des Caraïbes s’est trouvée au premier plan de cette traite négrière transatlantique (L. Peytraud, L’esclavage aux Antilles avant 1789, 1897).

III – La présence ancestrale des Kalinas dans les îles Caraïbes

La zone caraïbe connaissait une civilisation très ancienne, celle des Amérindiens (Arawaks ou Taïnos et Caraïbes ou Kalinago), de plusieurs millénaires avant JC. Cette population, stable depuis les V° et VI° siècles, menait une vie régie par la coutume et la propriété collective.

Lorsqu’en 1492, Christophe Colomb a abordé les îles, il les a fait connaitre comme « des découvertes », destinées à être conquises, ouvrant la voie au processus de destruction des civilisations existantes. Dès son second voyage en 1493, il a entrepris la colonisation de l’île dénommée Hispanola, qui est actuellement le territoire de la République d’Haïti et de Saint-Domingue."

(...)

Gilles Devers

Suite de l'article sur Alterinfo.net: http://www.alterinfo.net/Esclavagisme-Comment-la-Republique-francaise-a-agi-pour-maintenir-les-droits-des-anciens-maitres-esclavagistes_a113461.html

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.fr%2Furl%3Fsource%3Dimglanding%26ct%3Dimg%26q%3Dhttp%3A%2F%2Fp1.storage.canalblog.com%2F16%2F84%2F768961%2F87498879_o.jpg%26sa%3DX%26ei%3DxyJkVa-nLsXwUMD-gtAH%26ved%3D0CAkQ8wc%26usg%3DAFQjCNEBJfLrM47xccEbdcZmIaPoi8OGPA)

Indiens Mapuches exhibés au Jardin d'Acclimatation de Paris, photo de Pierre Petit, 1883. Source: http://colocolo.canalblog.com/archives/2013/06/12/27394300.html

Sur le même sujet:

Zoos humains et exhibitions coloniales - 150 ans d'inventions de l'Autre, par Pascal BLANCHARD, Nicolas BANCEL, Gilles BOËTSCH, Éric DEROO, Sandrine LEMAIRE. Editions La Découverte, 2011:

Ces zoos humains de la République coloniale : http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2000/08/BANCEL/1944

Sculptures sous-marines par Jason deCaires Taylor

Peru's mega-dam projects threaten Amazon River source and ecosystem collapse (David Hill)

David Hill a créé la rubrique "Andes to Amazon" http://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon dans le media britannique The Guardian, dans laquelle il informe régulièrement un vaste public sur la situation de l'environnement en Amérique du Sud. Dans ce nouvel article paru aussi sur le site écologique Mongabay.com, il nous parle des 20 barrages hydro-électriques en projet ou en construction sur le fleuve Marañon, dans l'Amazonie péruvienne, qui doivent servir à produire de l'électricité principalement pour les mines et l'exportation. Les conséquences sur l'environnement et sur les populations locales seront catastrophiques. Rappelons que les forêts primaires tropicales abritent 70% de la biodiversité terrestre (Francis Hallé) et de nombreuses populations aborigènes (Ñaupa Machu, en quechua: les ancêtres vénérables) vivant de la chasse, de la pêche et de l'agro-foresterie depuis des temps immémoriaux.

Pierre-Olivier Combelles

'The Marañón River in Peru where the government is proposing more than 20 dams on the main trunk.'. Photo credit: David Hill

| This article was produced under Mongabay.org's Special Reporting Initiatives (SRI) program and can be re-published on your web site or in your magazine, newsletter, or newspaper under these terms. |

|

|

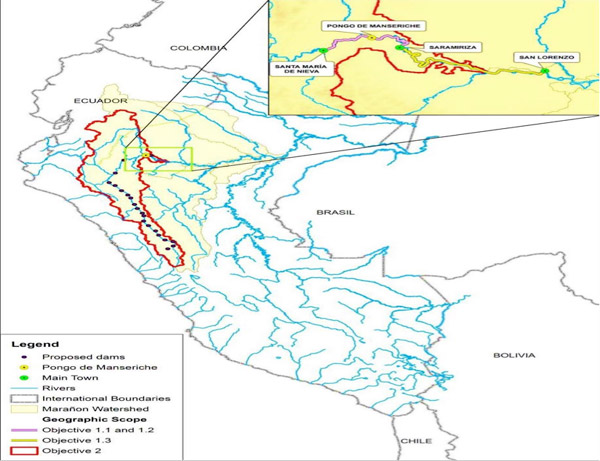

Peru is planning a series of huge hydroelectric dams on the 1,700-kilometer (1,056-mile) Marañón River, which begins in the Peruvian Andes and is the main source of the Amazon River. Critics say the mega-dam projects could destroy the currently free-flowing Marañón, resulting in what Peruvian engineer Jose Serra Vega calls its "biological death."

In 2011, Peru passed a law declaring the construction of 20 dams on the main trunk of the Marañón to be in the "national interest" and that the projects will launch the country's "long-term National Energy Revolution." But many Peruvians following the issue believe the planned dams are less about meeting "national demand" for electricity as the law reads, and more about supplying mining companies, and exporting to neighboring countries.

According to the government, the potential maximum demand for electricity is projected to be just over 12,000 megawatts (MW) by 2025, assuming very high growth rates are maintained. But the 20 Marañón dams alone listed in the 2011 law are expected to produce more than 12,400 megawatts, and that doesn't include the generating capacity of all the existing and other proposed dams in the Marañón Basin as a whole, and on other Peruvian rivers.

"Who is all this energy for? For people, or for the [mining] companies? The answer is: the companies," says Milton Sanchez, from the Plataforma Interinstitucional Celendina, a coalition of some 40 grassroots organizations based in the Celendin province of the Cajamarca region, which would be heavily impacted by the dams.

'Detail from a mural in the town of Celendin where opposition to the proposed Conga mine is high. Many people believe the proposed dams for the Marañón, like Chadin 2, are intended to supply energy to destructive mining projects, like Conga.' Photo credit: David Hill

'Detail from a mural in the town of Celendin where opposition to the proposed Conga mine is high. Many people believe the proposed dams for the Marañón, like Chadin 2, are intended to supply energy to destructive mining projects, like Conga.' Photo credit: David Hill

Serra Vega says that the construction of just four of the dams would destroy fish migrations and stop the deposition of vital nutrient-rich sediments downriver. These soils fertilize the crops on which thousands of Peruvians depend. "Studies show that when dams are built, 90 percent of the fish disappear. The main trunk [of the river] will die," says Serra Vega.

A 2014 report by the US-based NGO International Rivers (IR) agrees that the plans put the future of the Marañón at risk. IR used the sparse information available on the proposed dams to map potentially flooded areas. They concluded that the reservoirs created by the dams would inundate approximately 7,000 square kilometers (2,703 square miles) along 80 percent of the river's main trunk. "The currently vibrant and free-flowing river would be almost completely drowned," said the report.

One local resident whose house and land would be flooded by one of the many proposed dams - Chadín 2 - for the Marañón River Photo credit: Luis Herrera

Trouble flows downstream to the Amazon

International Rivers' Latin America Program Coordinator Monti Aguirre told Mongabay.com that the dams have been "poorly planned" and will cause "serious problems for the entire Amazon basin."

"There is no cumulative impact assessment, no trans-boundary environmental impact assessment, no accounting of the impact these projects would have on people's livelihoods and food production, and no study on how climate change will affect the performance of these projects," Aguirre said. "Serious studies could probably show that there is no need for any of them."

Paul Little, an environmental anthropologist, says that the Marañón dams could contribute to the Amazon's "ecosystem collapse", especially given that neighboring countries have similar plans for other rivers that birth in the Andes and feed into the Amazon.

'The Ameiva nodam lizard named to raise awareness of the proposed dams. It is one of many species discovered by German herpetologist Claudia Koch in the Marañón valley.' Photo credit: Claudia Koch

"The construction of many large-scale dams in the vast headwaters region of the Amazon Basin -- encompassing parts of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia -- will produce critical changes in continental water flows," states a 2014 report, Mega-Development Projects in Amazonia: A geopolitical and socio environmental primer, authored by Little. "This new wave of dam building in the headwaters of the [Amazon] Basin is a hydrological experiment of continental proportions, yet little is known scientifically of pan-Amazonian hydrological dynamics, creating the risk of provoking irreversible changes in rivers."

Little told Mongabay.com that Peru's plans for the Marañón could "provoke major disruptions in flooding cycles, fish migrations and sediment deposits throughout the Amazon Basin with potentially disastrous, but hitherto unknown, ecological consequences."

"These dramatic changes in continental water and sediment flows would also hinder the human use of the rich Amazon floodplains by traditional riverine communities," Little said.

Large dams cause multiple impacts

The negative social and environmental impacts of large dams have been acknowledged for many years. The World Commission on Dams reports that large dams are the "main physical threat" to the "degradation of watershed ecosystems" and destroy or restrict rivers' capacities to perform crucial ecosystem services such as providing habitat for fish reproduction, nutrient recycling, water purification, soil replenishment, flood control, and mangroves and wet-lands protection.

Dams also disrupt and destroy communities, displacing between 40 and 80 million people globally. "Whole societies have lost access to natural resources and cultural heritage that were submerged by reservoirs or rivers transformed by dams," the Commission states.

A dam construction team at work. Photo credit: Rocky Contos

The potential social impacts of the Marañón mega-dams would be enormous, forcing thousands of people from their homes, land and sources of livelihood. Many of these people include the indigenous Awajuns and Wampis. The destruction of fish migrations and of soil nutrients would harm fishing harvests and the cultivation of crops.

Loss of unstudied biodiversity and a world-class tourist destination

The dams and vast reservoirs would submerge cloud forest, dry forest and lowland Amazon rainforest, and areas extremely rich in biodiversity and high in endemic species. Many of the endemic species -- including mammals, birds, plants, insects, reptiles and amphibians -- haven't been studied by scientists.

German herpetologist Claudia Koch, from the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, discovered 14 species of reptiles and amphibians new to science in the Marañón valley in just 13 months of research. She told Mongabay.com that it isn't clear how many endemic species would be affected or "lost forever" due to the dams, because not enough is known about the species that have been described, no less the numerous species that remain "undetected."

'The proposed dams for the Marañón would destroy an embryonic tourist industry based on paddling and kayaking.' Photo credit: Rocky Contos

"Dams will cause fragmentation and habitat loss of many endemic species with localized ranges, creating barriers for [the sharing of] their genetic pool," said Koch, who named two of her discoveries Ameiva nodam and Ameiva aggerecusans ("reject dam" in Latin) after she learned about Peru's plans. "It's most likely that populations of many of the endemic species will decline in the near future," she said. "We don't know what will be lost if these dams are constructed."

An embryonic tourist industry would also be wrecked. Rocky Contos, a paddling excursion organizer and director of SierraRios, a U.S.-based conservation organization, calls the Marañón the "most precious river" in Latin America and "one of the finest in the world" for rafting and kayaking.

"The Marañón is on a par with the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon but nobody recognized that before I went down it and started publicizing it a few years ago," says Contos, who has dubbed a 550 kilometer (342 mile) stretch of the Marañón "The Grand Canyon of the Amazon." He says building so many dams on the main trunk would be "one of the greatest environmental tragedies in human history."

This newly discovered lizard species (Ameiva aggerecusans) is among 14 species of reptile and amphibian new to science recently found along the Marañón River. Researchers fear that the mega-dams projects will drown a treasure house of biodiversity. Photo credit: Claudia Koch.

How many dams?

Strange as it may sound, the exact number of dams currently proposed for the main trunk of the Marañón isn't clear -- making environmental and economic impact assessments difficult. The confusion is partly due to muddled policy and a lack of transparency by the Peruvian government, partly due to the fact that some of the studies on which plans are based date back more than 40 years, and partly because of the 2011 law. Some of the dams appear likely to overlap each other, and several appear to have had their names changed.

The 2011 law -- Supreme Decree No. 020-2011-EM -- calls the Marañón River Peru's "Energy Artery" and provides names for each of the 20 proposed dams, along with the amount of electricity each one could generate. These are exactly the same 20 dams identified in a 1970s evaluation of the river's hydroelectric potential:

- Vizcarra (140 MW)

- Llata 1 (210 MW)

- Llata 2 (200 MW)

- Puchca (140 MW)

- Yanamayo (160 MW)

- Pulperia (220 MW)

- Rupac (300 MW)

- San Pablo (390 MW)

- Patas 1 (320 MW)

- Patas 2 (240 MW)

- Chusgon (240 MW)

- Bolivar (290 MW)

- Balsas (350 MW)

- Santa Rosa (340 MW)

- Yangas (330 MW)

- Pion (350 MW)

- Cumba (410 MW)

- Rentema (1,500 MW)

- Escurrebraga (1,800 MW)

- Manseriche (4,500 MW)

The 2011 law doesn't include one dam, simply called Marañón, which is already under construction. Nor does it include at least four others -- Veracruz, Chadin 2, Rio Grande 1 and 2 -- which are at different advanced planning stages. All of these would be on the Marañón's main trunk. According to Serra Vega and other Peruvians following the issue, Veracruz has replaced the proposed Cumba 4 dam, and Rio Grande 1 and 2 have replaced the Balsas dam.

Moreover, the 2011 law doesn't include four proposed dams known as Marañón 1, 2, 3 and 4 which, says Serra Vega, would also all be located on the Marañón's main stem roughly between the proposed Patas 1 and Pulperia dams. IR's 2014 report states that the "exact location" of these four dams isn't known, but notes that engineers from the Generalima company were seen in the Patas 2 region in 2013, downriver from Patas 1. According to Serra Vega, Marañón 1 would effectively replace Patas 1, Marañón 2 would replace San Pablo, and Marañón 4 would replace Rupac.

In February 2015, Peru's Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM) confirmed that at least three of these dams have what Peruvian law calls "definitive concessions," granted by the government and required for the development of hydro-electric projects generating more than 500 MW. As acknowledged above, one of these, Marañón, is already under construction. According to OSINERGMIN, a government body supervising investment in mining and energy, Marañón was 28 percent built as of March 2015, and scheduled to start operating in December 2016.

The other dams that have "definitive concessions" are Veracruz and Chadin 2. According to MEM, Veracruz is scheduled to be built starting in June 2017 and begin operation in 2022, while Chadin 2 is scheduled to commence construction in March 2016 and operation in 2023. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for Veracruz was approved by MEM in 2013, after initially being rejected, and the EIA for Chadin 2 was approved in 2014, following extreme controversy and complaints from local people saying they had suffered intimidation, repression and criminalization of protest.

At least another two of the proposed or planned dams, Rio Grande 1 and 2, have been granted "temporary concessions," which are required to do feasibility studies. The EIA for both dams is currently being written and two rounds of "informative workshops" with local people have been held, with similar complaints emerging of intimidation, repression and criminalization of protest. In addition, Marañón 1, 2, 3 and 4 had "temporary concessions" which have now expired, according to Serra Vega.

The most controversial proposed dams

Easily the most contentious project to date is Chadin 2, which has met with fierce local opposition and would involve flooding numerous villages and displacing more than a thousand people.

'Segundo Vargas Machuka, one of thousands of people who live on the banks of the Marañón whose homes and land would be flooded by the proposed dams.' Photo credit: David Hill

Eduar Rodas Rojas, president of the Federation of United Rondas Campesinas in Celendin, told Mongabay.com that people are opposed to Chadin 2 because the agriculturally productive Marañón valley would be flooded and fish stocks destroyed, because the intention is to generate energy to supply the highly controversial Conga mining project, because it would change "our cultures and ways of life," and because "it will not bring us development."

"For us the only development is looking after the land and the water," said Rodas Rojas.

By far the biggest of the proposed dams is Manseriche, which could generate up to 7,550 MW, according to Peruvian President Ollanta Humala who offered that information during a presentation to a mining conference in Arequipa, Peru in 2013. Manseriche would impact many thousands of people, mainly indigenous Awajuns and Wampis, and could meet with far greater opposition than even Chadin 2.

In its 2014 report, IR estimated that the area flooded by a Manseriche dam generating just 4,500 MW could be 5,470 square kilometers (2,112 square miles), and its reservoir could drown an entire town and extend across the border into Ecuador. A 7,550 MW mega-dam would need to be even bigger.

Some of the spectacular scenery found along the Marañón River. Photo credit: David Hill.

Almost every Awajun and Wampis man or woman interviewed by Mongabay.com said they were opposed to, or seriously concerned about, the proposed dam at Manseriche. Some Awajuns said it could lead to conflict or a second "Baguazo," the name given to the initially peaceful protest by thousands of Awajuns and Wampis near a town called Bagua in 2009. Things turned violent there after riot police opened fire on the protesters. More than 30 people were killed, including over 20 policemen, and more than 200 injured.

"If they try to dam Manseriche and send in the army, we would be prepared to give our lives in defense of our forest," said Edgardo Aushuqui Taqui, former vice-president of the Aguaruna Domingush Federation, an organization representing Awajun communities immediately upriver from Manseriche. "We are not going to allow this to happen. This will be a second Bagua for us."

Energy for the people or for mining companies?

As mentioned earlier, the intention of the Marañón dams as stated in the 2011 law is to meet "national demand," but many Peruvians familiar with the dam projects believe that they have far more to do with supplying electricity to mining companies operating in Peru, and possibly creating an export market.

The bridge at Balsas, near a proposed dam site. Photo credit: David Hill.

Romina Rivera Bravo, from the Lima-based civil society organization Forum Solidaridad Peru, told Mongabay.com that MEM initially considered exporting energy generated by the Marañón dams to neighboring countries, particularly Brazil, but that has now changed.

"After the scrapping [in 2014] of the Peru-Brazil energy agreement [signed in 2010], it's known that the majority of the projects will feed into the National Interconnected Electricity System (SEIN) to meet internal demand which will benefit, among others, the extractive industries, particularly mining," says Rivera Bravo. "But the possibility of exporting to countries such as Chile has not been abandoned."

President Humala explicitly made the connection between the proposed Marañón dams and mining at the Arequipa conference in 2013. He presented a map showing numerous copper and gold extraction projects in northern Peru along with several of the proposed dams: Manseriche, Rentema, Chadin 2, Cumba 4 (which is now Veracruz), and Balsas (now Rio Grande 1 and 2).

"With this map we can see how we can generate around mining a center of territorial development in the northern macro-region," Humala told conference attendees. "As we can see, gold and copper projects dominate this zone, which includes Piura, Lambayeque, Cajamarca and Trujillo. In order to operate, they need energy, and for that the construction of at least five hydroelectric power stations generating more than 10,000 MW is envisioned."

Some Peruvians following the issue connect at least one of the dams to specific mining projects. Rodas Rojas, from the Rondas Campesinas, told Mongabay.com that energy from Chadin 2 is intended to power the "big grinding mills to be installed at Conga," the highly controversial proposed expansion of the much-condemned Yanacocha mine run by the U.S.-based Newmont Mining Corporation. Newmont's partners are Peru's Minas Buenaventura and the World Bank's International Finance Corporation, which provided funds for initial construction and expansion and has a 5 percent stake. According to Lynda Sullivan, an Irish journalist based in Cajamarca, some of the personnel involved in promoting Chadin 2 and now Rio Grande 1 and 2, are former Yanacocha employees.

These rice fields upriver from the proposed Pongo de Rentema dam would be inundated by its reservoir. Photo credit: David Hill.

Almost all of the proposed dams under "definitive" and "temporary concessions" are controlled by foreign companies. Rio Grande 1 and 2 are under the direction of Odebrecht Energy Peru, a subsidiary of the giant Brazilian group Odebrecht, while Chadin 2 is under the auspices of AC Energy, another Odebrecht subsidiary. Veracruz is operated by the Compania Energetica Veracruz, a subsidiary of Chile's Enersis, which is controlled by Spain's Endesa, which is in turn controlled by Italy's Enel, according to BN Americas. Maranon 1, 2, 3 and 4 are all under the direction of Generalima, another En-ersis/Endesa/Enel subsidiary.

Killing the Marañón with dams?

The 20 dams proposed by the 2011 law, and the others under construction or in advanced planning stages described in this article, are all on the Marañón's main trunk. For the Marañón Basin as a whole, including tributaries, the total number of proposed dams is much greater. According to a 2012 research paper by U.S. scientists Clinton Jenkins, with the Brazilian NGO Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas, and Matt Finer, now with the U.S.-based Amazon Conservation Association, the total is 39 dams, but that doesn't include Rio Grande 1 and 2, nor Marañón 1, 2, 3 and 4, nor Vizcarra.

IR's 2014 report highlighted the government's serious failure to inform people about the proposed dams on the Marañón. "[T]echnical information… and the potential reservoir inundation extent of most of the projects has not been made available to the public," IR concluded. "This lack of transparency is unacceptable, given the dramatic impacts these projects will have to local people as well as downstream ecosystems and livelihoods that currently depend on a healthy and free-flowing Marañón River."

For more details on some of the planned or proposed dams named here -- Chadin 2, Rio Grande 1, Rio Grande 2, Manseriche, Escurrebraga and Rentema -- see forthcoming Mongabay.com articles by David Hill.

| This article was produced under Mongabay.org's Special Reporting Initiatives (SRI) program and can be re-published on your web site or in your magazine, newsletter, or newspaper under these terms. |

May 11, 2015

A mural in the town of Celendín opposing the proposed Conga mine. Many people believe dams like Chadín 2 and Rio Grande 1 and 2 are intended to supply electricity to mines such as Conga. Photo credit: David Hill

A mural in the town of Celendín opposing the proposed Conga mine. Many people believe dams like Chadín 2 and Rio Grande 1 and 2 are intended to supply electricity to mines such as Conga. Photo credit: David Hill | This article was produced under Mongabay.org's Special Reporting Initiatives (SRI) program and can be re-published on your web site or in your magazine, newsletter, or newspaper under these terms. |

OTHER REPORTING BY DAVID HILL

Peru's mega-dam projects threaten Amazon River source and ecosystem collapse

|

|

"I don't want to sell my land because I've lived here since I was 17," declared 82 year old María Araujo Silva. "This was where my children were born. I want to die here. That's why I'm not in agreement. I'm not in agreement with the dam."

Araujo Silva is outraged at plans by Peru's government and Brazilian company Odebrecht to build a hydroelectric dam just downriver from her village, Huarac, on the Marañón River. She says it would flood her home, her neighbors and the land where she grows coconuts, oranges, avocados, mangoes, limes, manioc and maize.

"No one around here agrees with it. No one," she told Mongabay.com. "An [Odebrecht] engineer says the reservoir isn't going to flood us, that we don't need to be worried, but I don't believe him."

Araujo Silva shares her mud-brick home with José Chacon Carrascal. He too is against the dam. "They say it'll bring us work, but I already have work in my chacra [small farm]. I don't agree. What would we do?"

An anti-Chadín 2 mural in the nearby town of Celendín. Photo credit: David Hill

Rio Grande 1 and 2: "no agreement"

Huarac is in the middle Marañón valley – the central section of a 1,700-kilometer (1,056-mile) long, free-flowing river that begins in Peru's Andes and is the main source of the Amazon River.

Declared the country's "Energy Artery" by law in 2011, the government is proposing to build over 20 dams on the Marañón's main trunk, and possibly double that number in the Marañón basin. One dam just downriver from Huarac, Rio Grande 2, and another just upriver, Rio Grande 1, would be two of the first to go ahead. Together they could generate 750 megawatts (MW) of electricity.

Many of Araujo Silva's neighbors feel similarly about the dams. Head downstream, along a windy unpaved road, and you come to the tiny settlement of Saumate where Angelica María Araujo lives alone, cultivating papayas and other crops to support herself and her daughter studying in the nearby town of Celendín. "No one is in agreement," she said. "Where are they going to move us to?"

Araujo Silva's niece, Aurora Araujo Dávila, lives in Celendín but owns several hectares in Huarac where she grows avocados, mangoes, papayas and oranges. "All this would be flooded by Rio Grande," she said. "These were my father's lands. I want to leave them to my children. Local people say they're not going to let the company in."

Of course, not everyone objects. Manuel Briones Perez, who says he has worked for Odebrecht, is in favor of the dams, like "many people", like the "majority" of landowners. The project will bring benefits, he claims, including 8,000 jobs, education, reforestation and better roads. "Why wouldn't we be in favor? Here we're forgotten. The state doesn't reach here," he said.

Map showing the proposed locations of the Rio Grande 1 and 2 dams and the area that would be flooded. Credit: Odebrecht/Amec (Peru) S.A.

Odebrecht: Short on information, long on rumor

Confusion about Rio Grande 1 and 2 is rife. Some people interviewed by Mongabay.com claimed to know details, like where the dams would be built and how high they would be, although those details varied from person to person. Others appeared to know little or nothing, or are confused by contradictory or changing facts.

"There's no clear information," said Victor Vargas Machuko, from Palenque, located at Kilometer 17 on the road running upstream from a village called Balsas. "They're misleading us. The engineer Cesar [Gonzales, from Odebrecht] said it would be flooded between Kilometer 5 and Kilometer 16 -- then Kilometer 18. Then the company said the dam would be 50 meters high, then 60, and the second dam would be 120 meters high, then a maximum of 130, but then it changed to 165."

According to María Chavez Mendina, another Palenque resident, 50 percent of local people are in favor of the dams, 50 percent against.

"But there's no type of information," she said, "People just say we'll be relocated. What we want is information from the company. Clear information. That's what we're asking for."

In search of the truth

A "temporary concession" for Rio Grande 1 and 2 was granted by Peru's government to Odebrecht Energy Peru, a subsidiary of the giant Brazilian Odebrecht Group, in November 2014. That gave the company the green light to do feasibility studies for both proposed dams.

What was initially an anti-Chadín 2 message in the surrounding countryside. The 'No' has since been rubbed out and replaced with 'Yes.' Photo credit: David Hill

The concession area runs for approximately 60 kilometers (37 miles) north to south, across the Amazonas, Cajamarca and La Libertad regions. It includes portions of Celendín, San Marcos and Cajabamba provinces, and numerous districts such as Utco, Jorge Chavez and Oxamarca.

Amec (Peru) S.A., a subsidiary of the United Kingdom-registered Amec Foster Wheeler, has been contracted by Odebrecht to write an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the dams. The EIA must be approved by Peru's Energy Ministry (MEM) before construction begins.

Odebrecht has held two rounds of community meetings as part of the EIA process, but people interviewed by Mongabay.com were fiercely critical. They said the company has sabotaged meetings in various ways -- by choosing days when many people couldn't attend, by unmooring boats so others couldn't travel, and by repeatedly failing to turn up at scheduled times and places.

Interviewees also said that some meeting participants voicing concerns about the dams have been insulted, intimidated and silenced. According to several sources, there was violent conflict at a meeting in one settlement, Jecumbuy, in March.

"There are people who are in favor who insult us. Those in favor insult those who aren't [in favor]," said Vargas Machuka.

A mural in the town of Celendín opposing the proposed Conga mine. Many people believe dams like Chadín 2 and Rio Grande 1 and 2 are intended to supply electricity to mines such as Conga. Photo credit: David Hill

Community meetings: "80 percent are from elsewhere"

Arguably the most serious allegation against Odebrecht is that it loaded the community meetings with people who live elsewhere. Some Mongabay.com interviewees said that this was to give the impression that many people support the dams.

"They bring [them] from other places, but [those people] have nothing to do with it," said a woman from Huanabamba, a village adjacent to Huarac, who didn't want to give her name. "They're not us. They don't own land here. They're the ones in agreement, but they don't have anything to do with here."

Some people claim that these outsiders are paid to attend the meetings, or that they work for Odebrecht or mining companies who stand to benefit from the electricity generated by the dams.

Eduar Rodas Rojas, president of the Federation of United Rondas Campesinas in Celendín, which would be impacted by both Rio Grande 1 and 2, called the outsiders "bought people."

"They photograph them," said Rodas Rojas. "They're from elsewhere. With these photos, they trick the government into thinking local communities agree."

The middle Marañón valley. Photo credit: David Hill

Lidman Chavez Pajares, president of the Front for the Environmental Defense of Oxamarca in Celendín, said that Odebrecht has also tried to trick the government by collecting "fraudulent" signatures at the meetings "to make it look like lots of people attend." He claims that some of the people signing at the meetings work for Gold Fields, a South African company running the Cerro Corona mine in Cajamarca, and Yanacocha, which runs the much-condemned Yanacocha mine and is made up of the U.S.-based Newmont Mining Corporation, Peru's Minas Buenaventura and the World Bank's International Finance Corporation

"But 80 percent are from elsewhere," Chavez Pajares asserted.

Socorro Quiroz Rocha, from the Association for the Defense of Life and the Environment (ADEVIMA), agreed with that assessment. She said that approximately 80 percent of the people who attended meetings in Limon, Utco, Jorge Chavez, Oxamarca, Huanabamba, Jecumbuy and Balsas were outsiders, with some coming from as far as 200 kilometers (124 miles) away.

Others put that percentage even higher. One man from Huanabamba who didn't want to give his name told Mongabay.com that at one meeting 90 percent were outsiders. "They don't let the people from here speak," he said. They only let the people from outside speak."

According to one attendee at the March meeting in Balsas, just downriver from the Rio Grande 2 site, it was "almost entirely people from outside."

Asked for its response to these accusations, Odebrecht emailed Mongabay.com that there "would be no reason to bring participants from other regions" and it is not a "practice of our organization."

Dam opposition is also being muted in other ways. Some people are afraid to "speak openly" because they say they've been threatened, and at least two men, Absalon Martes Velasquez and Nazario Chavez Tirado, face criminal charges.

Dams like Chadín 2 and Rio Grande 1 and 2 would flood extensive agricultural areas where fruits such as papayas are cultivated. Photo credit: David Hill

"This is about criminalizing protest when they are simply exercising their rights," said Quiroz Rocha.

"The aim is to intimidate people, to scare them," Chavez Pajares said, "so they don't continue with the struggle."

Rio Grande = major negative impacts

At a meeting in Huanabamba in November, Odebrecht's Cesar Gonzales said that the Rio Grande 1 dam would be 150 meters (492 feet) high and flood 38 square kilometers (14 square miles), while Rio Grande 2 would be 50 meters (164 feet) high and flood 6 square kilometers (2 square miles), according to ADEVIMA's Quiroz Rocha. Asked by Mongabay.com to confirm which areas would be flooded, the company sent a map showing that the entire river and valley from the site of Rio Grande 2 upriver -- almost the length of the whole concession -- would be underwater.

That, said Chavez Pajares, would flood "large extensions" of forests and valleys producing avocados, bananas, oranges and coconuts, among many other crops. "We don't know exactly how much [land would be flooded] because no studies have been done," he said, "but it would be more than 3,000 hectares (7,413 acres) of dry forest."

Cesar Chavez from Tupen village, which would be flooded by Chadín 2. Photo credit: Rocky Contos

Chavez Pajares said the impact on the Marañón River itself would be disastrous, "killing" fish stocks and stopping nutrient-rich sediment moving downriver. In addition, flooding would drive many unique, endemic species extinct and the stagnant waters of the reservoir would also generate methane gas "20 times more contaminating than carbon dioxide," contributing to climate change.

"Our position is the following: no to the dams because they'll destroy our valleys, threaten our identity and culture, contaminate, and supply mining companies," Chavez Pajares said. "There are other ways to generate energy: small hydroelectric projects, solar and thermal energy."

Chadín 2

Rio Grande 1 and 2 are far from the most contentious of the proposed dams for the Marañón, nor the most advanced.

Just downriver from Rio Grande 2, beyond Balsas, is the site for a proposed dam called Chadín 2 and, just downriver again, is the proposed site for Veracruz. Both have "definite concessions" required for the development of hydroelectric projects generating more than 500 MW, and their EIAs have been approved by MEM.

Local resident Angelica María Araujo in Saumate: 'No one is in agreement. Where are they going to move us to?' Photo credit: David Hill

Chadín 2 is expected to generate 600 MW and has met with fierce opposition from local communities and elsewhere in Peru, as MEM itself has acknowledged, as well as internationally.

Like Rio Grande 1 and 2, the operating company, AC Energía, is an Odebrecht subsidiary, and Amec (Peru) S.A. wrote the EIA. The concession area includes parts of the Amazonas and Cajamarca regions, and the Celendín, Chachapoyas and Luya provinces. According to the EIA, the dam would be 175 meters (574 feet) high and flood 32.5 square kilometers (12.5 square miles).

"Stagnant lakes" from the Andes to the Amazon

The potential impacts of Chadín 2 are similar to Rio Grande 1 and 2, but arguably more numerous and more serious. Extensive croplands and over 20 villages would be flooded, and more than one thousand people forced to abandon their homes, land and sources of livelihood. Many more villages and people would be impacted indirectly.

In addition, as Peruvian engineer José Serra Vega noted in a cost-benefit analysis written for the Lima-based civil society organization Forum Solidaridad Peru, Chadín 2 would mean deforesting 12,000 hectares (29,652 acres), emitting greenhouse gases, and causing "biodiversity loss and the severe alteration of the aquatic systems, with the interruption of the flow of river sediments and the death of fauna and flora."

The dam would also flood pre-Hispanic archaeological ruins and destroy an embryonic tourist industry based on paddling and kayaking, which has led to a 550 kilometer (342 mile) stretch of the Marañón being dubbed "The Grand Canyon of the Amazon."

Benjamin Webb, founder of Paddling with Purpose, an international organization coordinating with local NGOs, said Chadín 2 will impact the section of the Marañón "most similar to the Grand Canyon of Colorado."

"Once you cut the flow, you cut the opportunity to have a long, uninterrupted river journey which is what makes this place so special," Webb said. "If the other dams are built, there will essentially be no river left to paddle, only a series of stagnant lakes from the Andes to the Amazon."

"Totally rejected"

Opposition to Chadín 2 has been growing since 2012. Local defense fronts and alliances have been formed, public statements made, meetings and protests held, a petition and campaigns launched, media alerted, and reports published, with organizations such as Forum Solidaridad Peru, Cooperación and the Cajamarca-based Grufides involved.

On the walls of houses that would be flooded, and in nearby Celendín, Cajamarca and the surrounding countryside, painted murals and messages have appeared declaring "No to Chadín 2" and "Marañón River without Dams."

Local resident María Araujo Silva in Huarac: 'This was where my children were born. I want to die here.' Photo credit: David Hill

In late March, the Front for the Defense of the River Marañón (FDRM) issued a statement that Chadín 2 "is totally rejected by landowners in the Marañón valley", calling it a "criminal project" that would put lives at risk. "We're not going to sell our lands for neither gold nor silver," it stated.

Rodas Rojas, from the Rondas Campesinas, told Mongabay.com that "every base and community" rejects Chadín 2. He said this is because the Marañón valley's crops and fish stocks would be flooded, because the intention is to generate energy to supply the controversial Conga mining project run by Yanacocha, because it would change "our cultures and ways of life," and because "it will not bring us development."

"For us the only development is looking after the land and the water," said Rodas Rojas.

According to the Plataforma Interinstitucional Celendina (PIC), a coalition of 40 grassroots organizations, between 90 and 95 percent of the region is opposed to Chadín 2. That could be even higher in some areas, said Benjamin Webb, after visiting Balsas and other potentially impacted villages such as Tupén and Mendán this March.

"We interviewed many local people to find out what their thoughts are," Webb said. "We went in hoping to get a balanced set of interviews, representing both sides, for and against the projects. This proved to be impossible. Almost everyone in these communities is opposed."

The middle Marañón valley. Photo credit: David Hill

In Tupén, Dionisia Huamán told Webb that "they came here and said they wanted to flood our valleys and build a dam on the Marañón. We were really concerned about that. We really love our river."

In Balsas, Jeyson Tirado complained that "people here don't want to know anything about Chadín. It will affect their zone, their lands and animals."

In Mendán, Juan Peña responded with outrage: "they treat us as ignorant just because we're against Chadín 2. We're not against them. They just have to respect our properties, our rights."

Criticisms of Chadín 2's EIA process are similar to those emerging for Rio Grande 1 and 2. These again include Odebrecht bringing outsiders to meetings, and the criminalization of protest. More than 60 people are being "investigated or prosecuted criminally for questioning the legitimacy" of the project, according to a report by U.S.-based NGO Earthrights International.

"We're being denounced and persecuted for defending the water, our lands, our cultures, and our rights," Rodas Rojas told Mongabay.com.

Other criticisms include people being threatened, Odebrecht spreading misinformation about the project, and police attending meetings and barring access to some people.

Will Chadín 2 go forward?

In an email to Mongabay.com, Odebrecht wrote that it is currently "finishing technical and socio-environmental studies" at Chadín 2, and, according to MEM, construction will start next year.

However, many local people say Odebrecht can't currently enter the region. When a team from Peruvian TV program Cuarto Poder visited last year and "found no one in favor of Chadín 2", they caught three Odebrecht representatives on camera who had just been detained by local people.

"The project can't go ahead as long as we decide not to sell our lands," reads the FDRM's March statement. "We don't accept entry by the company or its operators."

![Local resident Victor Vargas Machuko: 'There's no clear information [about the proposed dams].' Credit: David Hill](https://mongabay-images.s3.amazonaws.com/15/0504_dh_Rio-Grande-Victor-Vargas-Machuko-David-Hill.2.jpg)

Local resident Victor Vargas Machuko in Palenque: 'There's no clear information [about the proposed dams].' Photo credit: David Hill

Peruvian engineer Serra Vega now questions whether the proposed Marañón dams will proceed as scheduled, given current economic conditions in Peru, the huge amount of private investment required, and a possible reduction in medium-term domestic electricity demand. That is to say nothing of, in Chadín 2's case, the "very strong problems" Odebrecht has with local people.

In addition, Serra Vega notes the "mysterious" absence of both Chadín 2 and Veracruz from an electricity sector presentation in March showing long-term expansion of hydropower in Peru. Both dams featured in a similar presentation the year before.

"What it could mean is that these projects are going to be delayed," he told Mongabay.com.

That possibility could bring some hope to Marañón valley residents whose homes are threatened by the Rio Grande dams or Chadín 2. "Whether we're flooded or not, my idea is that they'll force us to leave here," says Edith Ortiz, a schoolteacher in Huanabamba. "What will we do?"